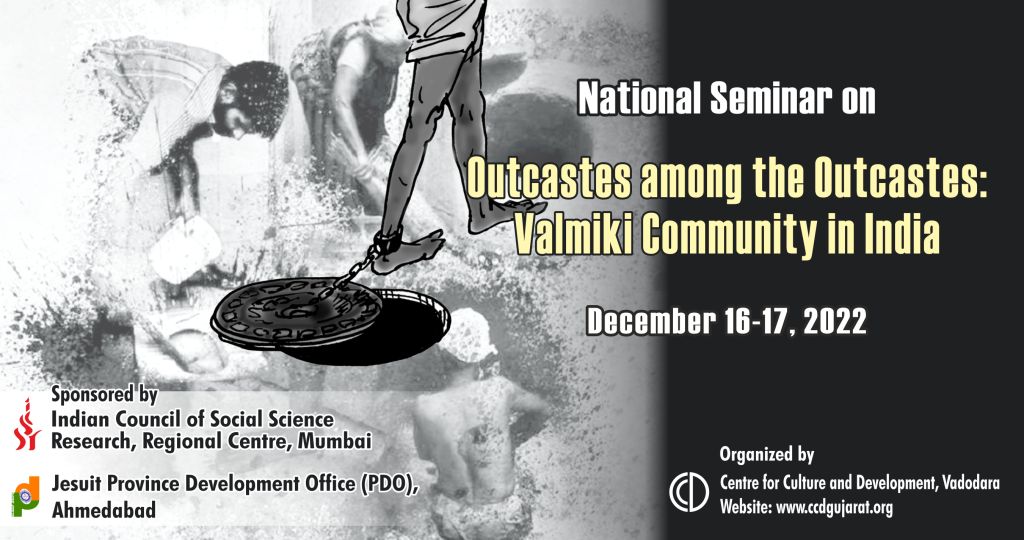

![]() National Seminar

National Seminar

“Outcastes among the Outcastes: The Valmiki Community in India”

(December 16-17, 2022)

SUMMARY

India is a caste-based society. Even today, the varna-caste as a social system determines the nature and characteristics of socio-economic and political life of many Indians. The outcastes or the Dalits are the most discriminated against and excluded social groups. However, the Valmiki among these Dalit communities are the worst exploited, excluded among the outcastes facing the worst kind of discrimination especially due to their occupational practice. Untouchability is practiced against them by most castes and even by the other Dalit groups. Even today, the Valmiki’s are isolated, compelled not to use public spaces, public utilities, and services; discriminated against, and deprived of equal access to social and economic opportunities. In this context, the Centre for Culture and Development (Vadodara) organized a two-day National Seminar on ‘‘Outcastes among the Outcastes: The Valmiki Community in India’ to address the status and situation of the Valmiki community in India.

The seminar commenced with watering a plant, symbol of nature by dignitaries namely Dr. Denzil Fernandes, Prof. P.M. Patel, Prof. Chaya Patel, and Director of the CCD Dr. James C. Dabhi. Post this formal inauguration, Dr. James gave an introductory address.

In his introduction address, James talked about the relevance of the Seminar citing that in a caste-based Indian society the discriminative varna-caste system is so well established in the mindset of Indians that even education and exposure to other countries, societies, and cultures have not erased this inhuman ideology and practice. The Avarna/outcastes/Dalits are the most discriminated against but the Valmiki among these communities are the worst exploited and excluded. They are considered the ‘lowest’ of the discriminated Dalit hierarchy as they are engaged in cleaning and sanitation related occupations. They are compelled to clean filth, human and animal excreta, disposing of dead and rotten bodies of animals, cleaning private and public latrines, cleaning gutters manually, etc. Even today, the community is isolated, discriminated and marginalized socially, economically and politically. According to him, their social exclusion must be seen from the articulation of political, social, economic and spatial dimensions. He pointed out that by bringing people from various fields together for a discussion, sharing and listening to views on the Valmiki community, better insights into the socio-economic reality of the community would develop. It would not only bring out the intricacies of the status of the community in present times but could be a unique contribution to the sociology and anthropology of Dalits in India.

The Key Note Address by Denzil Fernandes, highlighted that Valmiki’s are the lowest among the Dalit castes due to their engagement in ‘unclean’ occupations. They are included in the list of Scheduled Castes along with other scheduled castes, however, their socio-economic conditions are worse than other Dalit communities. Though untouchability against scheduled castes is abolished, the Valmiki's are still faced with the inhuman practice, in the form of discriminatory behavior and attitudes from others. There are several welfare schemes for Scheduled Castes, including the Valmiki’s, but there is hardly any improvement in their social status. Rather than the annihilation of castes advocated by Dr. Ambedkar we see its reinforcement partly unfortunately due to affirmative actions. According to him, a serious reflection on the various factors that prevent the social emancipation of the Valmiki is needed. He argued that in order to achieve social emancipation of the Valmiki community, there is a need to re-imagine their caste identity, culture and socio-economic life. For social emancipation, education is the key as it can change their status to some extent but access is also filled with struggles. Access to welfare schemes can be helpful but lack of awareness among the community continues their backward status. According to him to weaken the caste Dr. Ambedkar proposed the ‘annihilation of caste’, while others proposed the ‘reformation of caste’, but we need to move towards the ‘de-hierarchization of caste’. For him, Caste is a social category, it should be de-linked from occupation, religion, and ritual symbols in order to achieve the possibility of social mobility in the true sense.

The first session of the seminar chaired by Prof. P.M Patel had two research papers that focused upon the ‘The Occupational Stigma and Challenges of the Valmiki Community’.

Sanjay Solanki in his paper ‘Legal and Human Rights of the Valmiki Community: Indian Democracy and the Valmiki’s Struggle for Equality and Dignity’, brought out the fact that the Valmiki communities are yet to achieve equality in Indian democracy. They are struggling for equality and dignity in social spheres. They are deprived of their rights to access various public places and diverse occupations due to their occupational identity; as a result, the community represents a group that is socially, educationally, economically, and politically backward. He suggested that to change this, we require steps like providing free education to the children of Valmiki’s, providing free housing and medical facilities to the community as well as increasing their political representation. He also argued for the separate reservation for the Valmiki as well as their co-option at all levels of political bodies.

Shama Mehrol’s paper ‘Caste, Gender, Labour and COVID-19: Corona Warrior Frontline workers (Formal and Informal) Safai Karamchari Valmiki Women in Ulhasnagar, Maharashtra’, focussed in-depth narrative of women safai karamcharis and their lived experience of doing safai-kaam (cleaning work) and extended duty hours at the time of COVID-19. It highlighted how they had to face additional difficulties during the Covid pandemic, due to their involvement in caste-based occupations with the intersection of class and gender. She stated that these women faced multiple discrimination during the Covid pandemic - being a woman, a Valmiki, and maintaining distance in the name of social distancing. All these multiplied their experience of untouchability mainly due to the stigma of pollution attached to the work of safai-kaam. According to her, when understood in the context of women, such stigma also has its roots in patriarchy and caste, where women are considered to be impure and made responsible for cleaning work both inside and outside the house irrespective of caste, class, and geographical area. It was highlighted that safai-kaam is passed on to the younger generation of married women, especially from mother-in-law to daughter-in-law so that they can work alongside. Furthermore, besides extended work hours, women reported handling care-work and household chores leading to extra pressure on them with no time for themselves. Health and Hygiene during Covid- 19 was another issue that the women faced and had to deal with. During this period, their own health remained the last priority while they struggled to keep their families safe from Covid infection as they were compelled to travel by ordinary transport and commute from home. According to author, though safai-karamcharis were labeled ‘Corona Warriors-frontline workers’, this gestures was only tokenism, without any material benefits, helping in improving their living conditions. Rather they were living their lives constantly under exposure to health risks, unfriendly behaviour, and exploitation due to the nature of their work.

The second session of the seminar chaired by Prof. Nandini Manjrekar had three papers that focused on the ‘Change and Continuity in Status of the Valmiki Community’.

Sriti Ganguly in her paper ‘Changing Educational Status and Aspirations of a Dalit Community in Delhi- A Case of Balmikis’, highlighted that owing to their caste-based occupation. The Valmiki are recruited as sanitation workers, at the same time, they also continue to be spatially concentrated in caste-based bastis and mohallas (habitats) spread across the city like Delhi where the study was based. It highlighted how ‘samaj’, ‘sangat’ and ‘mahaul’, play a role in shaping educational aspirations, trajectories and experiences of the young generation of learners as well as allow understanding of the enabling and restrictive factors. The paper explored the intergenerational changes and continuities in educational access and choices of the Balmikis. It was observed that parents made their children go to school and think about their progress rather than seeing them get absorbed in collecting garbage. However, in spite of this the school dropouts were high among the group due to various factors. For instance, caste-based remarks continue to shape the learning experience of Balmiki students along with the differentiated schooling structure of poorly maintained government schools and elite-English medium private schools. It was pointed out that the link between neighbourhood and schooling especially for marginal communities was important. She raised the issue that lack of cultural capital in terms of a support system, guidance, and mentorship are a few accumulated disadvantages that are holding the community back. According to author mere physical proximity, without a compatible socio-cultural milieu, cannot make education an attainable dream for the Balmikis.

The paper by Anshika Srivastava, ‘Educational Experiences and Aspirations among the Balmikis in Delhi: An Exploratory Study’, looked at some aspects pertaining to the education of ‘Balmikis’. It was pointed out that there was a tendency among scholars to look at the Dalits as a homogenous group, but the reality is that it is not. Balmikis face challenges and the stigma of ‘untouchability’ due to their engagement in work considered as ‘polluted’. Also owing to their hereditary occupation, levels of education among the group remain low, and that largely restricts them to move to different type of employment and better manual work. While exploring the educational aspects of the community, the paper highlighted that they lag behind other Dalit castes in education, especially in the schooling of children. For those children who are in school, the majority of their parents were still doing sweeping and cleaning work, but the parents did not want their children to enter the same occupations. Children also held a similar view. Both generations groups aspired for salaried employment – the ‘most respected work’, which they could achieve through education. Education was seen as a tool to gain respect and break the stigma along with making a child knowledgeable, polite and a well-mannered person. Such views, made parents strategize for a child's academic success seen in terms of arranging tuition, attending school meetings, building social networks, right links and so on. Children did not want to enter the work of parents, but the structural constraints in terms of accessing the schools sometimes weaken this hope. She stated that caste discrimination was inherently inbuilt in the school setting manifested through ‘teaching - learning and student-teacher relationships’. Caste based prejudices and stereotypes were observed in terms of derogatory remarks and selective mention of parents/community’s occupation for children’s academic failure or behaviour. In her view, education though opened opportunities for the Balmikis, structural constraints and learning experiences sometimes bind to realise the possibilities that could have been made available to the community.

Rakhi Dhaka in her paper, ‘I am a Valmiki: My Life- My Story' - Personal Narratives’, shared her experience of being and developing as an educated woman from the Valmiki community. She shared how culture, caste, gender and class got reflected in her experiences of being a ‘woman’ and a ‘Valmiki’. She stated that being a female research scholar from Dalit community throws open the questions of power and control leading to exploring the social psychological questions of self-worth and the sentiments that constitute identity. She also said that there is a need to establish the lived experience of the community so that it can generate knowledge production - a sort of theory for Valmiki discourse by the Valmiki. She also talked about her struggle to deny her identity as a Valmiki out of being shamed and acknowledging her identity and experiencing the inner freedom by not internalising the discrimination practiced by others.

Deepak Katariya and Rashmi Pal’s paper, ‘Sustainable Development Goals and Valmiki community: A Critical Note’, discussed, how the status of the Valmiki community in relation to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are at opposite ends in terms of decent work, good health, well-being, quality of education and access to basic amenities with reference to safai-karamcharis working at Delhi University. The paper showed that workers had to do their job without safety equipment, there was an extra burden of work because of less manpower, their wages were delayed which in turn affected workers' household finances and expenses despite cleaning other places, their own bastis were in poor conditions. It was mentioned that barriers like home, poverty, social status, and perceptions about the community are very much present. Even if educated people think of occupational mobility, the location of their residence/settlement becomes a hurdle, as job recruiters avoid hiring them, thereby re-imposing them to continue with their traditional occupation of cleaning. Authors argued that despite, various schemes and policies for Valmiki emancipation, the challenges and struggles of the community have not changed much. Moreover, they are continuing this work due to social pressure and livelihood. In their view, access to education and awareness about various acts/schemes meant for them will lead to their betterment.

Alok Verma’s paper, ‘Status of Valmiki Community in Uttar Pradesh’, discussed the condition of the Valmiki community in Uttar Pradesh. His paper highlighted that Valmiki War in Hathras in a protest of gang rape and murder of a 19-year-old Valmiki girl and the reinforcement of indigenous equipment by the Ambedkarites have shown resilience and hope among the Valmiki. The discussion also detailed out through case narratives, the discrimination that Valmiki’s faces in educational institutions such as schools and colleges. For instance, they had to sit separately during midday meals in school, they could not play with the rest of the children due to their caste, discriminatory behaviour by instructors during training, and so on. The paper also highlighted that the Valmiki were becoming politically conscious, creating opinion-forming Dalit network in Uttar Pradesh, though not at the scale of Jatavs. In general, they have emerged as a Dalit vote base for the BJP. He also raised questions like who is representing the community. What were the reasons for their backwardness? Whether revisiting the community and helping them was possible? Why do the elite groups within the community ignore the peer community?

Parshottam Vaghela’s presentation, ‘Current status of Valmiki Community’ narrated the inhuman practices against the community, which he has observed and experienced himself being a Valmiki and his association with the Valmiki community as a human rights defender. Since he largely worked for manual scavengers, it was pointed out that many Valmiki had died while cleaning sewers but they had not received attention from the government and civil society. He stated that in such cases of deaths no FIRs are registered and no criminal cases are filed against these employers. According to him, death in sewers should be seen as atrocities against Dalits and treated in the same manner. He also mentioned that there was no political participation and unity in the community. He also cited a few cases where the inhuman nature towards the Valmikis by other caste groups was exposed.

In his paper, ‘Socio-economic Change and Continuity among Valmikis in Gujarat’, James C. Dabhi, highlighted some of the preliminary findings of the ongoing study of the Valmiki community of Bhal region of Anand District of Gujarat undertaken by the Centre. It was observed that the status of higher education among them is poor; the majority had kucccha-pucca houses and are mostly farm labourers and marginal farmers. It was also stated that over the years, the community had shown certain changes in the spheres of education, living condition, economic situation and social status. However, there were certain aspects within the community and villages that showed continuity. The education level had increased up to the higher primary, more girls ere literate, yet there was lack of awareness for education for better life choices. He said that one found improvement in housing structures and physical amenities, but the physical location of Valmiki residences in villages were still at the periphery with poor streets/roads. The community has seen greater migration for employment but ending up largely in the traditional occupation in the cities. Physical atrocities though reduced, the practice of untouchability was still practiced in different ways. The feudal system- ‘client-family’ relationship was still prevalent in some of the households, where they provided services to the Bharvad and Darbar (Rajput, Jhala) families who happened to be land-owning, economically well-off castes with political connections.

The first session of the second day began with the theme of ‘Modern India Vs Modernity – Practice of Exclusion and Inclusion, chaired by Dr. Sanjay Solanki with three presentations.

Arjun Kumar’s paper, ‘Swachchh Bharat Abhiyan (SBA) and Valmiki Community: A Relation of Contradictions’, highlighted the stigma and practice of ostracization of the Valmiki community due to their traditional occupation of manual scavenging, its impact on the self-esteem of the community and undermining the dignity of labour. The occupation they are in is not their choice but forced on them by the Hindu social order. The paper mainly looked at the experiences of the Valmiki community in light of the Swachchh Bharat Mission - the biggest sanitation mission of the current government. The discussion showed how the competition of ‘Indian clean city ranking system’ had disowned the recognition of communities that actually clean the cities. Pointing out the history of glorification of scavenging and sanitation work both by Gandhi and Narendra Modi as the noblest service to society showed a flaw in their perspective. Arjun argued that the perspective they held was filled with social stigma and discrimination that even lead to hazardous diseases and death of people. Citing narratives of the manual scavengers, the paper discussed their lived experiences filled with inhuman hard work added with extra burden and job insecurity which affected them psychologically. On the question of why they are still doing the traditional job and not leaving it, the author argued that for them it was not about leaving their present occupation or negating identity but most importantly it was about their very survival. Critiquing SBA, it was said that the mission had promised to eradicate manual scavenging by 2019, but that is far from being achieved. It was pronounced that crores of toilets were built, but the question lay in whether they were connected properly to septic and sanitation systems that eliminate the need to clean them manually. There is no data on providing the sanitation tool kits to the manual scavengers. Manhole workers still enter the sewer bare hand without any protection gears. According to him, the eradication of manual scavenging under SBA is a myth, as ground reality presented a different picture. SBA has become more of a photography event for the government and celebrities. However, there exists an ugly picture behind the white-wash, which no one wants to talk about or concern about.

Mukesh Thakur’s paper ‘उतर उदारीकरण के युग में वाल्मीकि समाज, जाति और हाथ से मैला उठाने की प्रथा’, stated that even today the Valmiki society was a victim of the caste system, exploitation and untouchability. The biggest example of this was that even in the age of modernization, the practice of manual scavenging still existed. Change of religion, power and economy have not been able to put an end to the practice. The paper mainly looked at the detailed analysis of the causes of manual scavenging and the social, economic and political aspects that perpetuate the practice of manual scavenging. It was highlighted that the concepts of purity and impurity perpetuate exploitation of the Valmiki as they engaged in manual scavenging. To a certain extent since they form a group of cheap skilled labour available to do unclean work, the development of modern facilities and infrastructure for sanitation is a low priority. The paper also raised questions that why in times of modernization and technology, a group of people is forced to do manual scavenging. Whether we lack money, or lack of technology or the root cause for such practice lies in the caste system. Whether urbanization has strengthened manual scavenging? Whether poverty can be blamed for their poor social status? For eliminating the practice of manual scavenging he suggested a few options such as wide publicity of quality education among them and a need for additional jobs so that they can be moved out from manual scavenging, wide awareness and strict implementation of laws meant for them, basic infrastructure should be reconstructed and cleaning works should be completely mechanized and lastly heavy investments should be made in the field of cleanliness.

The paper by Sumit Aujainwal, ‘सामाजिक संबंध और स्वच्छता का ज्ञान-विज्ञान: रेलवे के दिल्ली और जयपुर मंडलों में असंगठित स्वच्छकारों की कार्य स्थिति’, centred around the sociology of hygiene. It highlighted that the most relevant issue for the Valmiki’s are the interrelationship between social distancing and disposal of night soil symbolizing dirt, which is considered an impure act and also the main factor in spreading many infectious diseases. The paper looked at this debate of pure and impure with special reference to the unorganized safai-karamcharis of Indian railways at three levels, namely in the contexts of the sociological discourse of caste, of sanitation, labor relations, and colonial discourse and of Swachh Bharat Abhiyan (SBA). It was observed that efforts are being made to keep the stations, platforms and trains in a properly maintained and clean condition as far as possible. However, the regular cleaning of platforms, foot over bridges, cleaning of tracks, smooth arrangement of aprons, etc. remain as problems and challenges, as in many cases it required cleaning by hands. Moreover, due to the lack of manpower at many junctions, temporary sanitation workers have to do more work for less salary. The paper also made a critical reflection on the SBA such as how it neglects the people who are doing cleaning work of dry latrines, railway tracks, block drains, etc., toilets built under the mission are traditional toilets, and how it ignores the continuation of manual scavenging to large extent. The author proposed some interventions that could bring out some changes in the community. For instance, more weight be made towards replacing traditional toilets with bio-toilets to end the involvement of manual scavengers, a national wage policy for safai-karamcharis should be implemented besides providing them safety kits, encouraging machines and robotics technology for cleaning work, and a need for Sustainable Sanitation Development i.e. a sanitation development which is socially, economically and ethnically acceptable,

The second day concluded with the concluding address given by Dr. Nitin Gurjar on ‘Manual Scavengers in India’. He said that manual scavenging which refers to the practice of cleaning, carrying, and disposing of human excreta manually is the most inhuman way to treat human beings. There are acts to prohibit the practice of manual scavenging since the 1970s but nothing has improved much. Sewers are still cleaned manually by the workers without any protection that risks their lives to accidents and deaths. Stating census data his address mentioned that there are more than 07 lakh dry latrines in India, with Uttar Pradesh having the most and Andaman Island with the lowest. There are around 7,40,078 households where human excreta is removed by human beings. Moreover, there are 182,505 households in rural India with at least one member doing manual scavenging, which means the same number of people being manual scavengers in the country. His address also talked about a few discrepancies in the survey on manual scavengers in 18 states carried out by the Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment with help of the National Safai Karamchari Finance and Development Corporation. For instance, identified scavengers were much fewer in numbers as it included only 100 districts across the states out of more than 700 districts, there were also issues with the number of registered manual workers v/s as reported by districts/states. On the health of manual scavengers, it was highlighted that they suffer from respiratory disorders, typhoid, skin and blood infection, etc., in fact, a sewer worker dies at an average age of 32 years, and very few lived till retirement age i.e 62 years. It is a fact that sewer and sanitation workers are exposed to dangerous gas such as methane, carbon dioxide, ammonia, etc. leading to asphyxia, and a primary cause of death in manual scavengers. On this Supreme Court remarked that ‘sewers are the gas chambers where manual scavengers are sent to die’. He mentioned that, this is ironic that many workers die while cleaning sewers, but the reported death cases by the state authority generally remain low. The speaker also stated that the efforts of Safai Karamchari Andolan v/s union of India, had made the government pay compensation of Rs. 10 lakh to the family of a dead sewer worker, but in reality, one finds pending cases of disbursing compensation amount to the family as a big issue. In most states, more than 90% of families are yet to receive their compensation. He concluded his address by citing that in spite of various issues, the Indian government is looking for ways to eradicate manual scavenging through mechanization for which it had collaborated with the Robotic Start-up Company (Kerala) and municipalities in 10 states. However, how much they have succeeded in fulfilling their promises is another aspect that needs deeper analysis.

The ensuing discussions post presentations at each session raised important issues and concerns with respect to caste in general and the Valmiki community in particular. Some of them are:

- The social structure of caste is so deeply rooted that losing identity is very difficult.

- The perspective towards caste system changes depending on where one is placed- upper hierarchy would see it with greatness, while those at lower ladder would see it with contempt

- The notion of touchability v/s untouchability reflected through stigma is the main core of the caste system.

- Even after 75 years of constitutional rights and legislation, the Valmiki community are still facing various atrocities against them and struggles to achieve dignity and equality.

- There are various laws and commissions created for the emancipation of the Valmiki, but unless they are effective their existence is meaningless.

- Raising a voice about inhuman treatment against them is difficult as the Valmiki community is scattered and not unified.

- The internalization of self-oppression, of self-identity by the community needs to be broken.

- The need for civil society to become aware of the problems of the Valmiki community. There is a need for empathy than sympathy.

- Building up knowledge sources about the community by the people belonging to the same community through their lived experience. It may bring out the reality ‘of the people’ and ‘by of people’, helping in better understanding and ways to solve their struggles and challenges.

- Institutional discrimination is very much prevalent but in different forms. For instance, in school- it gets visible in the form of taunts referring to the occupation of parents.

- For many, education has become a source of change. It gives a way to employment and respect, thus enabling many to break away from the traditional occupation associated with the community. However, it is equally important to note that though education can bring dignity, erasing social stigma seems difficult.

- There is a lack of role models in the community.

- Better off Valmiki people should come forward to help the needy from the community as a ‘payback to society’ to continue the cycle of Valmiki emancipation.

- Along with cultural celebration there is also a need to celebrate the work of the community.

- Inclusion of gender in caste discourse is needed.

- There is a need for dignity among the Valmiki- not upper caste dignity but a conscious dignity as an individual right.

- Need for mobility through supportive measures-through government, civil society, or others.

- Need to generate surveys that are academically oriented to get a much better picture of the Valmiki’s situation and struggles.

- Representation of the community should be increased especially through academia

- Uninspiring response of the intelligentsia community to come forward and help the community is an important concern.

The discussion also raised important questions to ponder upon. Such as:

- Whether delinking of caste and occupation is possible?

- Whether reservations or affirmative actions strengthen caste identity or stigmatizes the community?

- How one can see the role of the state in the inferior/inhuman status of the Valmiki people?

- Whether declassification of Dalits according to sub-caste can bring in any change for the community? Whether it will allow the advantages of the reservation to reach the Valmiki to its fullest?

- How do non-schedule people look at the issues of Valmiki?

- What is the role of environment, company/companionship and society in the Valmiki's current social status?

- Whether acceptance by the community that they were born to do ‘traditional occupation’ and ‘only source of livelihood left’ hinders breaking caste identity and their social mobility?

- Can positional mobility be understood as a broader understanding of social mobility?

- Whether, leaving the traditional occupations and moving to new ones, would ensure it is free from stigmas and identity labels? Whether there would be a flow of people ready to take their new services irrespective of their castes?

- Whether mechanization of cleaning dirt is possible in order to solve the problem of the Valmiki community- identified for their occupation?

- Whether intercaste marriages can be a solution to weaken untouchability? If so at what cost?

- Whether a celebration of Valmiki Jayanti, holidays, building temples, etc are conspiracies to stay in the Hindu fold or are the new forms of discrimination?

In sum, the seminar was an intensive academic attempt to highlight and address various issues, challenges, and understanding of the ‘lived’ lives of the Valmiki community. It helped in raising better insights into the socio-economic reality and intricacies of their status in present times.

Add Comment